What the FPU?

What the FPU?

Technologies:

- Plotly

- Numpy, Pandas, etc.

- Whatever I used to build the new system for doing rollouts on games (WSL 2, C++, Bazel, Jax, PJRT, CUDA, …)

FPU

Many seemingly arbitrary algorithmic impacting the search and the statistics behind the AlphaZero algorithm can influence the way the model learns and behaves. As I was testing a new system I built to perform fast rollouts on the game of 5 in a row, I could not help but notice something odd about the search statistics: whenever it was the 2nd player to move, there would always be hundreds of child nodes with very few (usually just 1) visit. Why?

Following some pondering, I began to suspect a setting I had already heard of, but never thought too hard about: FPU1

The FPU (first play urgency) describes how the “Q” value of a MCTS child search node should be assumed should the node have no visits. The range of numbers Q can take is in [-1, 1], where -1 represents that this node is completely losing, and +1 represents a surely winning move. Interestingly, the implementation the authors of AlphaZero have chosen is to assume a value of 0 should the node have no visits (supplementary materials, gist):

def value(self):

if self.visit_count == 0:

return 0

return self.value_sum / self.visit_count

Which also happened to be what I did. Why, then is this parameter so disputed?

Why does FPU=0 result in a more diffuse node visit distribution for the second player?

The answer is because I only looked at the first few moves of each game, and because the second player is inherently disadvantaged in the game of 5 in a row. In fact, this phenomenon can actually be observed the more general case – when the player to move is in a disadvantaged position. This causes moves with visits to typically have a $Q \le \text{FPU} = 0$, thus deluding the MCTS into believing that the unvisited actions, no matter how low of a probability assigned by the policy, might offer better winning chances than moves it has considered already. This leads the MCTS to wastefully explore unlikely moves whenever it is evaluating a worse position.

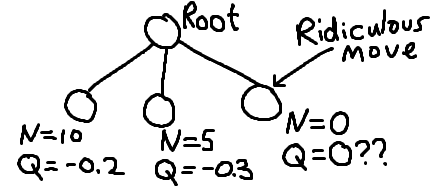

Just to really illustrate what happens, suppose the search find itself in this situation:

As the search ponders which node it should visit next, it sees that one node in particular has a substantially superior Q value to everyone else. Ignoring all other information – that the position is inherently disadvantaged, and that the move in question has an absurdly low probability from the policy, it inevitably would not be able to resist spending just a few playouts on that node. This is a problem as being wasteful in a NN-driven MCTS can greatly reduce the depth of the search tree and worsen evaluation. Think of it this way – on half the moves in the search tree, you’re going to waste about over 200 playouts on bogus moves, and you only have a total budget of 400~800 playouts for the whole search.

What is the FPU meant to be anyways?

Perhaps more egregiously, given a state $s$, setting an unvisited action $a$’s $Q(s, a) = 0$ does not make sense, as if we consider the initial case where none of the nodes have been visited yet, then $\forall a: Q(s, a) = 0$. Yet, we contradict ourselves when we assign the value function’s evaluation of the state $V(s) \ne 0$, as $V(s)$ is roughly fitted to model $\mathbb{E}_a[Q(s, a)]$. At a high level, we should at least let $Q(s, a) = Q(s)$ when we have no further information about that action. Indeed, this is what the likes of Leela Chess at KataGo do, albeit they usually do something like $Q(s, a) = Q(s) + f(N(s))$, with the general idea to penalise/boost $Q(s, a)$ as more visits $N(s)$ are accumulated on the parent node. This will then be parameterised further through some injective $f: \mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{R}$.

It then begs the question: Can we make a good guess for the FPU, with a good statistical foundation? Is there a good guess $Q(s, a)$ when $N(s, a) = 0$? Well, in an attempt to answer the question, I ran a number of selfplay games without policy noise in the search but with sampling on the moves, and collected about 100K positions. I also got addicted to Plotly’s 3d plots.

Off the bat, we have the NN output of policy $P(s, a)$ (I can’t render math on the plot), and value estimate of the root $V(s)$. Could we then get an estimate for what $Q(s, a)$ might end up being?

Eyeballing the result, it seems that the mean value for $Q(s, a)$ is usually some shrunken value of $V(s)$. The reason why is up to speculation – I couldn’t come up with a convincing reason, but I attempt to offer a couple of explanations for 2 observations:

- The reason $Q(s, a)$ is not as opinionated as $V(s)$ (i.e., it is closer to 0) is because the output of the value function is generally quite noisy.

- The reason $Q(s, a)$ is flatter when $V(s) > 0$ is because the only thing random, low-probability moves will do in winning positions is make you not win, but the opposite can’t be said for losing positions.

- Doing a linear regression, the fit $Q(s, a) \approx 0.7 \cdot V(s) + 0.4 \cdot P(s, a) - 0.2$ makes reasonable sense and makes for a reasonable fit too! We expect the result to show that $Q(s, a)$ being positively correlated with both of the other variables here. These values are also easy to obtain at any time, and could possibly be integrated into the training process.

Since the most important final output is the number of visits a child gets $N(s, a)$, we can also investigate its relation to the policy and value outputs on the root node.

Impressively, the policy proves to be quite a good estimator for the number of visits a child will receive. Despite the data being biased in this example (because the policy itself helps drive the search), this is still a pleasant result to see. Other than that, I don’t really have any comments. I mostly put the plot here because I thought it looked cool.

How this FPU value affects learning

We can see a substantial difference in the entropy based on the move number. Indeed, when it is the 2nd player to move (move 9), the search yields a much more diffuse distribution of visits to its child nodes. However, the misleading aspect here is that it is really not the move number, but rather the quality of the position that is the real predictor.

And a roughly equivalent box-plot: (Sorry if this doesn’t load… the JSON is quite large, and the browser doesn’t seem to reliably handle it!)

It should be noted that in the end, the playing strength of the model is still generally satisfactory. Indeed, we see this from the decent policy prediction of node visits, empirically from playing against the model, and that the value estimates are generally also quite consistent and accurate.

Anything else?

It’s easy to walk away from this thinking “I will not use FPU=0, and set the FPU to be the Q of the parent node” and not pay a second thought to this. While this is a popular approach with good empirical results in the open-source community, I would interject with just a couple of points:

- AlphaZero, allegedly using FPU=0, managed to achieve empirically strong results.

- Just because we can supply a “better” value for $Q(s, a)$ in the absence of any evaluations, it does not necessarily imply that the search will be better. What if this change reduces overall policy entropy, slowing down exploration of lower-probability moves? (Is this even good or bad?)

I think the moral here is that intuitively, providing a better estimate for $Q(s, a)$ has reasonable theoretical grounds for improving playing strength. However, until this is thoroughly tested, it’s hard to know if the change makes things better, worse, or makes little difference at all.

The catch is of course that people have tested this, and FPU seems to be an important parameter to tune to gain playing strength, which should be the ultimate goal.

-

It should be noted that FPU is not something that will show up in any of the AlphaZero series of papers, nor is it really even mentioned. FPU is a term primarily coined by the Leela Chess project. ↩