A Journey of Learning Reinforcement Learning

A Journey of Learning Reinforcement Learning

Technologies:

- Python

- PyTorch

The task

Snake is a fairly well-known game. In this game, you control a snake with the sole objective being to collect food. You should avoid directing the snake into the boundary or yourself as doing so results in a premature end to the game.

There have been many attempts to apply reinforcement learning to this domain, often with limited success (dying so early in a massive grid is an L result), though it’s also not too hard and has been solved by what I can only imagine as a lot of people.

The main goal for this project was really for me to expose myself to more reinforcement learning techniques and the theory and intuition behind algorithms like A2C and PPO which always seem to be out of reach of an average high school and university student. I say high school because that is where this journey started for me, and being able to finally recreate some results without cheating (no using existing RL frameworks), using only the theoretical knowledge provided by the papers and implementations only when necessary would be a satisfactory conclusion.

The theory

We need to start by making a few definitions.

- Let $s \in S$, the set of all states of a game (of snake, in this case). In practice, this will be some 1d or 2d array describing what is going on in the game.

- Let $\pi_\theta: S \to \mathrm{R}^n$ be a policy function mapping states to a probability vector representing potential actions. A higher probability should imply a higher quality action. It follows that at every point in time, there are $n$ available actions. This is a neural network, and its parameters are represented by $\theta$. *Note: I don’t bother masking illegal actions, but just make them have no effect on the game.

- Let $V: S \to \mathrm{R}$ be a value function mapping states to a scalar being the estimate of the sum of all future normalised discounted returns.

- A reward $r_t$ is a score given at a point in time $t$ by the environment. A return is the discounted rewards. Returns are calculated at the end of a game, and are constructed such that the return at time $t$, $\delta_t = \sum_{u=t}^{\infty} \gamma^{u-t} r_u$, where $\gamma$ is the discount factor and typically in the range of $0.95$ to $0.997$.

When you run a simulation of the game, you collect three pieces of data including the state, action you took, and returns $(s_t, a_t, \delta_t)$. You will (and should) accumulate many of these tuples. In the simulation, you sample your moves from the policy stochastically. (e.g., if $\pi_\theta(s) = \langle 0.2, 0.5, 0.3 \rangle$, then you have a $20\%$ chance to make the first action, and so on.)

A reasonable place to begin now is by learning how the heart of almost all policy updates work - the policy gradient method. Pretend you play 100 games of snake. You then calculate all the returns, and concatenate all the data together. Now you wonder to yourself - how do I determine whether I have made a good or bad move?

We can answer this by posing this scenario. One of the games you did well, and one of the games you did poorly. In the game you did poorly, the returns are are worse than that of the game you did well in. We could then attempt to make an assumption - the higher the return, the higher quality the move made at that point in time.

Now we have a very simple approach to constructing a way to update our policy. Normalise all the returns, and let those numbers be our ‘advantages’ $A$. i.e., $A_t = \frac{\delta_t - \mu}{\sigma}$. And update our policy to ascend on the function

\[\frac{1}{\text{num samples}} \sum_{t} \ln \left(\pi_\theta(a_t | s_t) A_t \right) = \hat{\mathbb{E}}_t \left[ \ln \left(\pi_\theta(a_t | s_t) A_t \right) \right]\]What?… would be what I thought when I first looked at this function. Let’s break it down.

$\pi_\theta(a_t | s_t)$ is the probability of making action $a_t$ at state $s_t$ under policy $\pi_\theta$. For example, if $\pi_\theta(s_t) = \langle 0.2, 0.5, 0.3 \rangle$ and $a_t = 3$, then $\pi_\theta(a_t | s_t) = 0.3$.

$A_t$ is the advantage of the action. We assume that if the advantage is positive, then it is a good move and vice versa. In this case, we have also normalised the values, so they have a mean of $0$ and a standard deviation of $1$. Ultimately, we want to be more likely to make more of a good move in the future, and less of a bad move.

Because we are doing an ascent over the function, note that if $A_t > 0$, then we want $\ln \left(\pi_\theta(a_t | s_t) \right)$ to go up (i.e., update $\pi$ to be more likely to suggest $a_t | s_t$). Conversely, if $A_t < 0$, then we want $\ln \left(\pi_\theta(a_t | s_t) \right)$ to go down (i.e., update $\pi$ to be less likely to suggest $a_t | s_t$). I’ve never bothered to think too hard about why the objective takes the log-probability, but I suspect it has its theoretical foundations in maximum likelihood, or because a linear difference in the log-probability represents a ratio - how many times more/less likely are we to make the move.

However, as you may already suspect, estimating the advantages to be a mere normalised version of the returns is not the best idea. There are certain states that inherently will give less returns - e.g., the snake is far from the nearest food, we are near to the end of the game, etc. Here comes the next idea.

Pretend this is the current state:

In this moment, you friend works out that this state should have a return of about $1.337$. However, you choose to steer straight down and into a wall, resulting in death. Your return ends up being $0$. From this, we can estimate the advantage of the move to steer straight down to be $A = 0 - 1.337 = -1.337$.

In practice, your ‘friend’ would be the value function $V$, which would itself be continually trained to be able to predict targets $V(s_t) \approx \delta_t$.

*Note: technically you won’t predict $\delta_t$ straight up, but normalise that value somehow so numbers don’t get out of hand. The loss is usually MSE or some variant (Huber, etc.).

This relatively simple innovation is at the core of the A2C method - the advantage actor (2 because there’s 2 A’s) critic. Referencing the analogy, you are the actor and your friend the critic.

By itself, you could probably get this to work and go on to beat the 8x8 snake game. However, it would be more interesting to take one more step and apply the theory behind PPO.

Let $\pi_{\theta_{\text{old}}}$ be the policy during the simulation, prior to any parameter updates during the learning step. We now define the probability ratio

\[r_t(\theta) = \frac{\pi_\theta(a_t | s_t)}{\pi_{\theta_{\text{old}}}(a_t | s_t)}\]This function tells us, for a sample $t$, how much our new policy $\pi_\theta$ differs in its evaluation from $\pi_{\theta_{\text{old}}}$.

Imagine we have a sample at time $t$, where during the simulation, the move that was played was $a_t = 3$, and $\pi_{\theta_{\text{old}}}(s_t) = \langle 0.2, 0.7, 0.1 \rangle$. Then, we update the policy a bit, and we want to know whether we should continue updating it, or a sufficiently large update has been applied. We evaluate $\pi_\theta(s_t) = \langle 0.15, 0.7, 0.15 \rangle$. In this case, $r_t(\theta) = \frac{0.15}{0.1} = 1.5$. We have increased the probability of playing move $a_t = 3$ in position $s_t$ by $50\%$. This is a lot!

This will be important because we want to know how much our new policy differs from the policy that played the training game, as excessively large policy updates are bad. Generally, PPO asserts that anything beyond a $20\%$ difference in the policy should not be further updated (if $r_t(\theta) > 1.2$ or $r_t(\theta) < 0.8$, then stop using sample $t$).

In the paper, all this reasoning is reasonably succinctly captured in the following objective function, which I have taken straight from the original PPO paper:

\[\hat{\mathbb{E}}_t \left[ \min \left( r_t(\theta) A_t, \text{clip}(r_t(\theta), 1 - \epsilon, 1 + \epsilon) A_t \right) \right]\]Where $\epsilon = 0.2$ arbitrarily by default. This function produces no gradients in the cases where

- $A_t > 0$ and $r_t(\theta) > 1 + \epsilon$, or

- $A_t < 0$ and $r_t(\theta) < 1 - \epsilon$

Those are the cases where we have made too great a policy update, and we need to stop doing so.

There’s also a couple other special sauces (because reinforcement learning is just notoriously full of these because it’s so unstable, difficult to get right, and feels more like art than science many times).

In practice, the situation can arise where $\pi_\theta(s) = \langle 0 \cdots , 0, 1, 0, \cdots 0 \rangle$ for most and if not all states. This is potentially bad because the policy basically becomes stuck on that evaluation. This leads it to produce low variety and novelty in its data, and worse, become stuck permanently on a potentially suboptimal policy.

To counter this, we add an additional term to the objective the policy is expected to maximise:

\[\hat{\mathbb{E}}_t \left[ \cdots + c_2 H(\pi_\theta(s_t)) \right]\]Where $H$ gives the entropy of a vector and $c_2 = 0.01$ arbitrarily by default. A vector like $\langle 0.25, 0.3, 0.45 \rangle$ will have more entropy that $\langle 0.1, 0.85, 0.05 \rangle$. This encourages the policy to be more ‘open’ to new ideas and explore more states during the simulation phase.

PPO also introduces a new way to estimate the advantages $A$ but compared to the other innovations is proposes, it isn’t really worth going over here.

The plan

Knowing all the math, it’s surprisingly simple to put all this into action with code.

Get our minibatch of data:

mb_states = states[minibatch_idxs]

mb_actions = actions[minibatch_idxs]

mb_old_log_probs = old_log_probs[minibatch_idxs]

mb_discounted_rewards = discounted_rewards[minibatch_idxs]

mb_advantages = advantages[minibatch_idxs]

For reference,

mb_states[t]= $s_t$mb_actions[t]= $a_t$mb_old_log_probs[t]= $\ln\left( \pi_{\theta_{\text{old}}}(a_t | s_t) \right)$mb_returns[t]= $\delta_t$mb_advantages[t]= $A_t$

We also need $\pi_\theta(a_t | s_t)$, and we will need $V(s_t)$, so let’s get those…

policy, value = net(mb_states)

policy[t]= $\ln\left( \pi_\theta(s_t) \right)$value[t]= $V(s_t)$

Compute the probability ratio $r_t(\theta)$.

ppo_r = torch.exp(

policy.gather(1, mb_actions) - mb_old_log_probs

)

ppo_r[t]= $r_t(\theta)$ by math

Now we have what we need to compute the objective

\[\hat{\mathbb{E}}_t \left[ \min \left( r_t(\theta) A_t, \text{clip}(r_t(\theta), 1 - \epsilon, 1 + \epsilon) A_t \right) + c_2 H(\pi_\theta(s_t)) \right]\]ppo_eps = 0.2

l_clip = torch.minimum(

# L^CPI

ppo_r * mb_advantages,

# clip(r, 1-eps, 1+eps) * A

torch.clip(

ppo_r,

1 - ppo_eps,

1 + ppo_eps,

)

* mb_advantages,

)

gain_policy = torch.mean(l_clip)

# Entropy bonus for policy

ppo_c2 = 0.01

gain_entropy = -ppo_c2 * torch.mean(

torch.sum(torch.exp(policy) * policy, dim=1)

)

gain_policy + gain_entropy= the objective to maximise

One last thing is to make the objective for the value function

# Earlier in code: mse_loss = nn.MSELoss()

loss_value = mse_loss(value, mb_returns)

loss_value= the objective to minimise

And bada-bing bada-boom

net_optim.zero_grad()

(-gain_policy - gain_entropy + loss_value).backward()

net_optim.step()

Job done. *Note that we subtract the gains, because PyTorch’s automatic differentiation and parameter update software expects us to provide a value to minimise.

The results

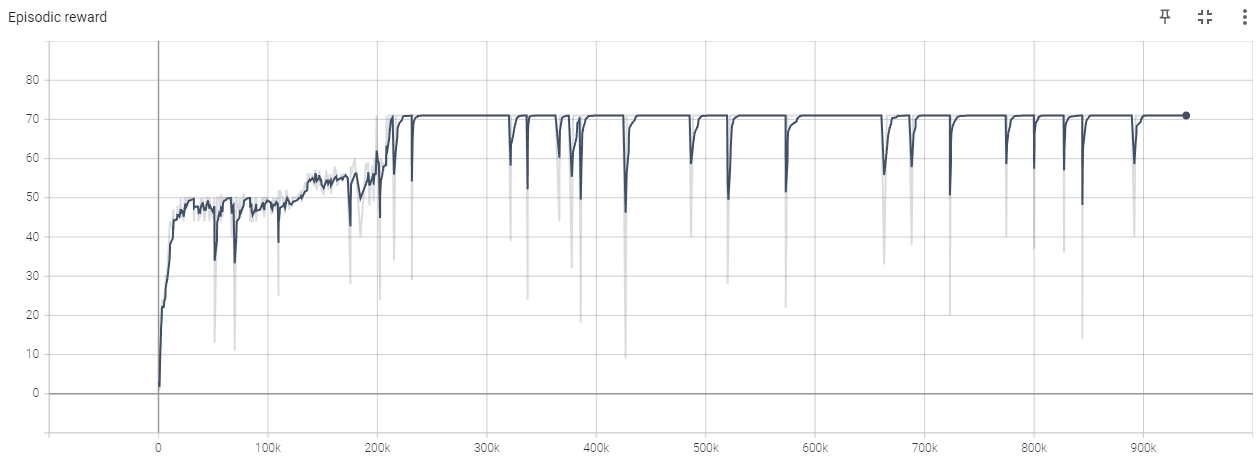

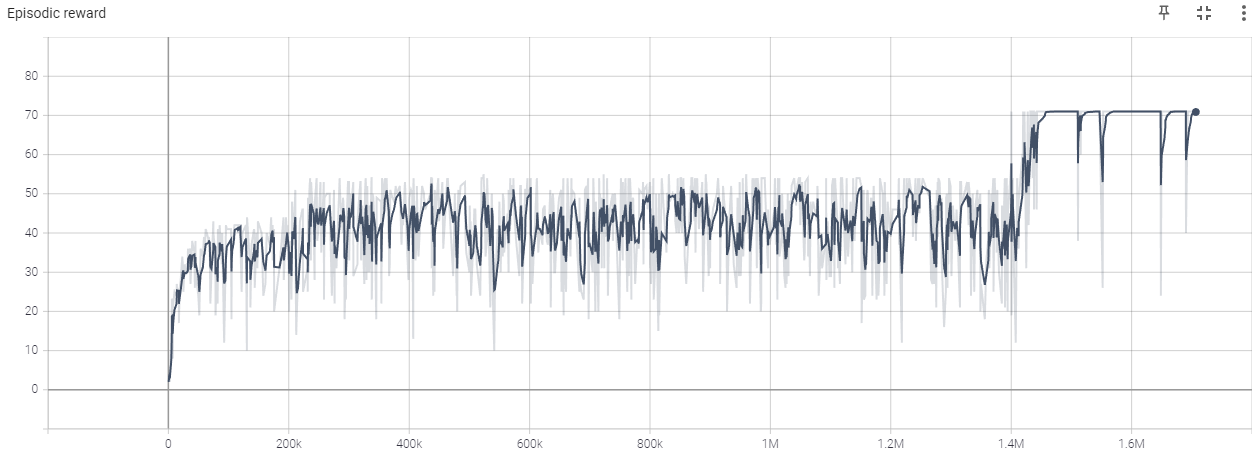

After much parameter tweaking and about a month-and-a-half of experimentation, I had 2 successful runs.

The maximum score is 71, as the agent gains 1 point for each food it picks up, and it can pick up a maximum of 62 pieces of food, and the final piece gives 10 points.

On the second graph, we can observe that the agent only reached peak performance 2 weeks after the start of training, and it did so seemingly randomly. This is just one example of the unpredictable tendencies of RL.

Let’s have some fun. The two games below are played by two neural networks whose training statistics were presented above. (Games stop when not visible on your screen to prevent your device from blowing up).