Behind the scenes - Curdle

Behind the scenes - Curdle

Technologies:

- Windows/Linux

- NVIDIA CUDA

- C++

The task

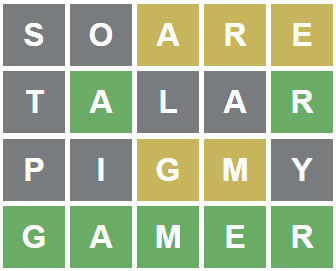

You might have heard of Wordle, which is a popular word game were users try to guess the secret word. Players provide guesses and the game informs whether each letter of a guess is

| Colour | Description |

|---|---|

| Grey | Incorrect. The letter does not exist in the word. |

| Yellow | Misplaced. The letter exists in the word but is out of position. |

| Green | Correct. The letter exists in the word at this position. |

Above: “E” and “V” don’t exist in the secret word, “L” exists but not at the start, and the secret word has “A” in the middle.

The objective of the game is to guess the secret word in as few guesses as possible. But how?

The theory

After having an initial go at the problem, 3Blue1Brown uploaded a video specifically about this topic and its relation to information theory.

The general idea is this:

- How close you are to finding the word depends on the number of possible answers remaining. For example, in the above scenario with the “LEAVE” guess, you can filter possible answers down to those that

- Do not have “E” or “V”

- Have, but do not start with “L”

- Have “A” as the third character

- A practical numerical measure is the number of bits of entropy, denoted $k$, where $2^k$ equals the number of possible answers $n$.

I take advantage of a few other facts about the game

- There is a fixed list of 2309 possible answers

- There is a fixed list of 12947 valid guesses - note that this list does not include the list of answers, even though they are valid guesses

At the start of the game, the entropy $k = \log_2(2309) \approx 11.173$. Now the question is, what answer gives us the best shot at reducing $k$ the most?

To answer this, define

The set of possible answers $A=\{ \text{cigar}, \text{rebut}, \dots \}$

The set of possible guesses $G=\{ \text{aahed}, \text{aalii}, \dots \}$

The state of the game $s_{a,\{g_0, g_1, \dots\}}$ where $a \in A$ is the secret word and $g_i \in G$ are guesses. Note that the start state would be $s_{a,\{\}}$

The entropy function of the game $k=\sigma\left(s_{a,\{g_0, g_1, \dots\}}\right)$

Now we need to find some guess $g \in G$ that minimises $\sum_{a \in A} \sigma(s_{a,\{g\}})$.

We can generalise this strategy to any state $s_{a,X}$, where $X$ is the set of all previous guesses. Let $U \subseteq A$ be the remaining set of logically possible answers.

\[\arg\min_{g \in G} \sum_{a \in U}\sigma\left(s_{a,X \cup \{g\}}\right)\]As you might suspect, applying this formula when the number of possible answers $|U|$ is very high (it starts at 2309!) might cause the program to take some time to figure out the answer. Even worse, $|G|=12947$. This is indeed a problem, which was the primary motivation for the next part of this project…

The plan

For this part we use a key insight, which is that the majority of the time is spent calculating the colours that the game will give for a particular word, and then filtering the list of answers based on those colours. To mitigate this, we can precompute a $12947 \times 2309$ matrix $L$ lookup table with the colours in each cell. Note that for this to work, $A$ and $G$ will need to have a specific order, which I assume starting from here.

Because Wordle is played over words with 5 characters and that there are only 3 colours, all 243 combinations of colours can be represented in $\mathbb{Z}_3^5$, or encoded as an 8-bit unsigned integer. In the end, our very big matrix only takes $12947 \times 2309 \times 1 \text{byte} = 29,894,623$ bytes to store (less than 30MB).

An example of the encoding scheme at work:

\[\text{Colours} = (\text{Yellow, Grey, Green, Grey, Grey})\]Then

\[\text{Vector} = (1, 0, 2, 0, 0)\]And the conversion to an integer is similar to that of changing from base 3 to base 10.

\[\text{Integer} = 1 \times 3^0 + 2 \times 3^2 = 19\]For the next part, define

\[\left(L_v\right)_{ij} = \begin{cases} 1 & v = (L)_{ij} \\ 0 & v \neq (L)_{ij} \end{cases}\]Example:

\[L = \begin{pmatrix} 1 & 2 & 3 & 1 \\ 2 & 3 & 2 & 3 \\ 1 & 1 & 3 & 2 \end{pmatrix}\] \[L_2 = \begin{pmatrix} 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 \\ 1 & 0 & 1 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 \end{pmatrix}\]Let $U \subseteq A$ be the remaining set of logically possible answers.

Let $\delta(j)$ return 1 if the $j^{th}$ answer is in $U$, and otherwise return 0.

\[\delta(j) = \begin{cases}1 & A_j \in U \\ 0 & A_j \notin U\end{cases}\]Let $\gamma(v,i)$ be the number of possible matches for the colour combination $0 \le v < 243$ and number representing a guess $1 \le i \le 12947$.

\[\gamma(v, i) = \sum_{j=1}^{|A|} (L_v)_{ij} \times \delta(j)\]Now we can define our objective:

\[\arg\min_i \sum_{v=0}^{3^5-1} \left( \frac{\gamma(v, i)}{|U|} \cdot \log_2(\max( 1, \gamma(v, i) )) \right)\]This works by multiplying the probability of seeing a certain colour combination by its resultant entropy, and summing over all colour combinations. However, in practice, it is more efficient to perform the division by $|U|$ at the end, or omit it entirely. The best word to guess is then $G_i$.

To make the algorithm perform better (especially when $|U|$ becomes small), a small modification can be made:

\[\arg\min_i \sum_{v=0}^{3^5-2} \left( \left( \frac{ \gamma(v, i) }{ |U| } \right) \cdot \log_2(\max( 1, \gamma(v, i) )) \right) - \gamma(3^5 - 1, i)\]This approach works well because:

- The number of iterations in the outer sum is 243, which is much less than the 12947 before. This gives us an opportunity to perform optimised vectorised operations on the inner expression.

- Computing $L_v$ is fast on GPU.

- Computing the sum of a row of a matrix is fast on GPU.

The implementation

All the CUDA kernels can be found in the source code, but I will explain the interesting ones here.

It should be noted that the matrix of unsigned 8-bit integers is casted to single precision floats as some operations only support this data type. Floating point precision is not an issue.

Vector equals (vector_eq_cuda)

This kernel is used in computing $L_v$ quickly. Even though $L$ is a matrix, to computers, matrices or any dimensional tensors are merely homogenous data stored in a contiguous array. For example, a matrix of shape $12947 \times 2309$ is stored as a continuous block of $12947 \times 2309 = 29,894,623$ elements.

This kernels essentially pretends the matrix is one huge vector. It takes an input va, a target value b, and outputs to vc. The size of the matrix (number of elements) is passed as the parameter n.

__global__ void vector_eq_cuda(float* va, float b, float* vc, uint32_t n)

{

int tid = blockIdx.x * blockDim.x + threadIdx.x;

if (tid < n)

{

vc[tid] = va[tid] == b ? 1.0f : 0.0f;

}

}

Vector magic (vector_times_max1_log2_cuda)

This kernel applies the function $f(x) = x \log_2(\max(1, x))$. It should be noted that the $1$ can be replaced with any value $0<z\le 1$ without any change to the operation of the function.

__global__ void vector_times_max1_log2_cuda(float* va, float* vb, uint32_t n)

{

int tid = blockIdx.x * blockDim.x + threadIdx.x;

if (tid < n)

{

vb[tid] = va[tid] * log2f(fmaxf(1.0f, va[tid]));

}

}

Sum matrix rows (SumRowsBLAS)

Not actually a kernel I wrote from scratch as it uses the cublasSgemm_v2 function to do the heavy lifting, but still interesting.

This function sums the rows of a matrix by performing a matrix multiplication with a column vector of ones. Mathematically, with a matrix $M \in \mathbb{M}_{mn}$ and column vector of ones $\mathbf{1} \in \mathbb{R}^n$:

\[M = \begin{pmatrix} a_{11} & a_{12} & \cdots & a_{1n} \\ a_{21} & a_{22} & \cdots & a_{2n} \\ \vdots & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\ a_{m1} & a_{m2} & \cdots & a_{mn} \end{pmatrix}\] \[\mathbf{1} = \begin{pmatrix} 1 \\ 1 \\ \vdots \\ 1 \end{pmatrix}\]Then

\[M \mathbf{1} = \begin{pmatrix} \sum_{i=1}^{n} a_{1i} \\ \sum_{i=1}^{n} a_{2i} \\ \vdots \\ \sum_{i=1}^{n} a_{mi} \end{pmatrix}\]Just one problem. cublasSgemm_v2 assumes we are storing our matrices in column-major format, when we are storing our matrices in row-major format! What’s the difference? Here’s an example.

- Row major: Data is stored as

[1 2 3 4 5 6] - Column major: Data is stored as

[1 4 2 5 3 6]

In other words, what we see as our matrix $M$ it sees as the transpose $M^T$.

But love math conquers all.

And because cublasSgemm_v2 also returns the result in column major format, we essentially compute

…and we are done.

The results

I’ve got the results in the readme of the repository, but here they are anyways. (Tested with my Ryzen 5 3600 and RTX 2060 Super)

| Implementation | filters/s | Seconds to suggest best word |

|---|---|---|

| My friend’s | 1.3k | Too many |

| Naive (Python/NumPy) | 13k | Loads |

| Naive (C++) | 170k | A decent amount |

| Precomputed word-pair colours (Python/NumPy) | 250k | 10-13 |

| Precomputed word-pair colours (C++/CUDA) | 1.4B | 0.002 |

And on today’s (20/05/2022) Wordle: